There has been confusion and argument over the date of the Battle of Carham, with some claiming 1016 rather than 1018 as the year in which the conflict took place.

Much of this confusion stems from a footnote on page 418 in the book, Anglo-Saxon England by the highly respected British historian Sir Frank Stenton. Stenton agrees with Simeon that Uhtred was killed in 1016, but he also claims that Uhtred led the Northumbrian forces at Carham. His reasoning, that names are better remembered than dates, give rise to his opinion that the battle was fought in the earlier date of 1016, and given his prominence as an historian, for many years, this view held sway

As evidence for the date, Simeon of Durham states that the battle was preceded by a comet, and after considerable research and with the help of NASA and the author of Cometography Gary W Kronk, it was determined that the only comet visible for decade around that time occurred in April of 1018.

If we can assume the Simeon was correct in the fact that a comet preceded the battle (although he was writing 100 years after the event) then this firmly places the battle of Carham in September of 1018 or perhaps a week or so later.

Today modern historians accept 1018 as the actual date if the battle.

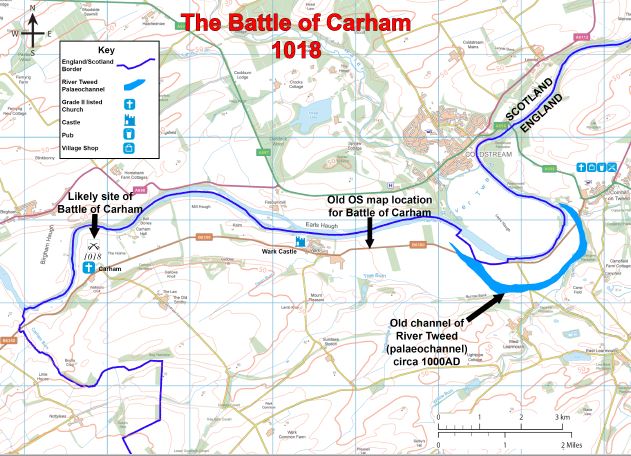

The local popular perception has for many years been that the battle was fought on the south side of the River Tweed just to the East of Wark.

There are several reasons for this point of view:

The battle is sometimes also known as the battle of Coldstream which is directly over the river from Wark.

There is the site of a ruined castle at Wark

The 1965 OS map marks the battle just to the east of the village.

However, all of this can be disputed. Later OS maps fail to mark the battle although one large scale OS map does have the battle in Wark but in 1016, and several mark 'battle place' near the castle but this refers to a skirmish between English and Scottish forces in 1370.

But the most compelling evidence the battle was not fought here comes from work done by Passmore and Waddington in their comprehensive Managing Archaeological Landscapes in Northumberland who conclusively prove that the river Tweed has significantly changed its course, and what today would appear as an ideal battlefield would, one thousand years ago, and even as late as the Battle of Flodden in 1513, have been river or swamp.

The construction of Wark Castle was not started until the 1100s and therefore had no significant influence on the Battle of Carham.

This evidence makes Wark an unlikely candidate for the site of the Battle of Carham.

At the time of the battle the village of Carham was the site of an important minster founded by St Cuthburt. This would have been on or very close to the site of the present parish church.

Cuthburt was an important cultural icon in the North and his minster would have made the site of his Minster a place worth attacking, and also worth defending.

Carham is on the line of an ancient Roman road linking Tweedmouth to Dere Street (A69 at St Boswells) and there was an important river crossing at Carham evidenced by the name of Birgham, the village on the northern side of the Tweed. An ancient pathway, which is still visible and often used, leads southwards from Birgham Church to a ford across the Tweed and a crossing of the river can still be made at low summer water levels. It is thought that a Roman patrol camp existed at or very close to Carham. Although the course of River Tweed has moved, and can be seen to be still moving within this area, the hard limestone rocks have kept this movement to a minimum. The flat, fertile and well drained flood plain to the South of the Tweed suggest a suitable place for battle and Carham is certainly a plausible site for the battle.

To date there has been no serious archaeology done to look for the battle site, but the existence of Cuthbert’s Minster and the ecclesiastical importance of Carham ate the most important factors that make this the more likely site for the battle of 1018.

If we accept Simeon's account the Uhtred was killed in 1016 then obviously he did not command the Northumbrian forces. His brother was known as Eadwulf Cudel, Cudel meaning 'Cuttlefish', a medieval insult meaning coward.

History is written by the victors, and it would therefore be a better story for the victors to have defeated the well known and respected warrior Uhtred, rather than his weak, vacillating and cowardly brother. Malcolm II would also have expunged his defeat of 1006 at Durham by defeating his one time vanquisher.

Simeon describes the Battle of Carham as a massive victory for Malcolm and Owen, and bewails the loss of the male population between Tees and Tweed, However the academic Meehan of Edinburgh observes that only Simeon makes this assumption of such massive losses.

There are no surviving accounts of the battle itself, but we can make an educated guess based on other similar conflicts of that era.

Armies were much smaller than in later battles, the numbers of soldiers more likely to be in hundreds rather than thousands.

The route that the combined army would have taken as they made their way eastwards is unclear. It would seem sensible that they took a route south of the River Tweed along the Roman road to Carham as no similar route was available north of the Tweed. However, this would have brought the combined army into enemy territory and more liable to attack by Northumbrian forces. An approach on the northern bank of the Tweed to Birgham would have afforded the river as a defensive barrier against such an attack.

River crossings were, and to this day are still military obstacles which can cause problems. A good defensive position can often be taken along a river bank and many battles were fought in these locations. The name Birgham indicates the existence of a river crossing point, in fact it is still possible (with great care) to cross the Tweed between Birgham and Carham at low summer water levels, However if Malcolm II and Owen arrived at Birgham before the Northumbrians had set up a defensive position, or if they had sufficient numbers to overcome such a position the River Tweed might not have proved to be an insurmountable problem.

There are no surviving accounts of the Battle of Carham, but we know the weapons and the tactics of the times and can deduce a likely scenario. Armies of the day were small, combatants usually numbered in hundreds rather than thousands. They travelled light, carried all there armaments and lived off the land by scavenging and plunder. Scouts would have noted the progress of threats or invasion, but response times might have been slow due to distances that had to be covered, first to get to muster points and then to march as a cohesive force to counter the enemy incursion.

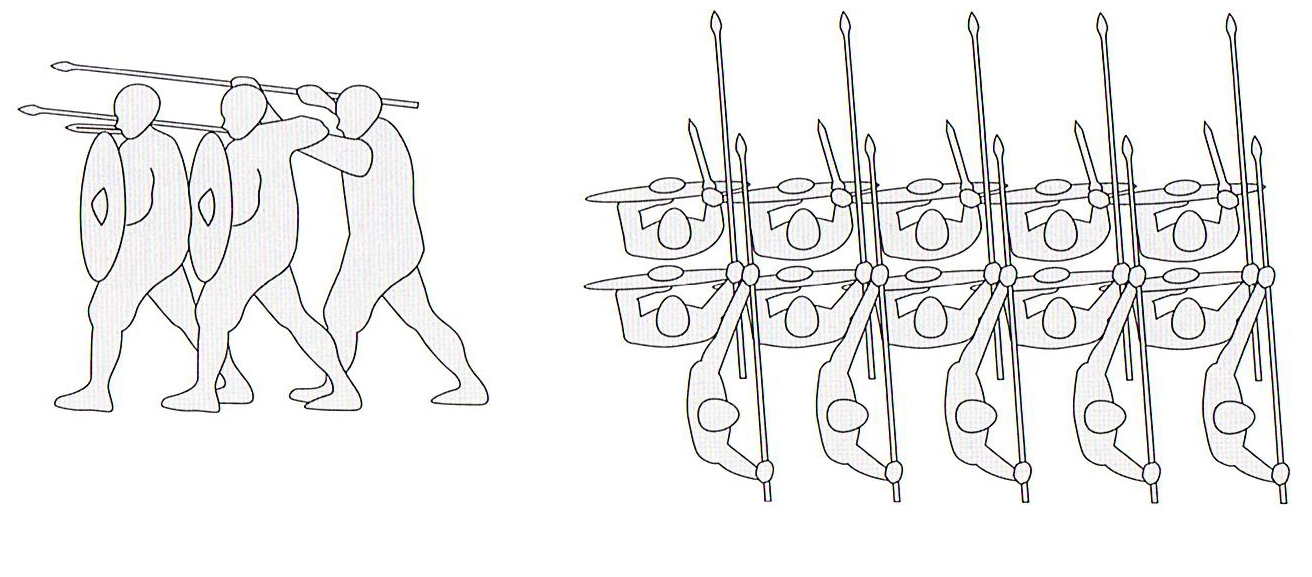

The weapons of war were very basic, hand held or thrown, and therefore causing close quarter fighting. The first weapons used in a battle were missiles; spear, javelin and arrows, but as battle proper was joined, heavy sword, axe and seax, a long dagger were used in close quarter, face to face and hand to hand fighting. Defensive personal armour was heavy, but surprisingly similar to the weight carried by the modern infantryman. It consisted of a large metal rimmed wooden shield, steel helmet and mail tunic, leather and linen padding.

Using these weapons while carrying the weight of the armour required prodigious personal strength and stamina, but ensured that battles were relatively short in duration as exhaustion would inevitably overcome ambition.

Battles were short, sharp, bloody and brutal.

The normal battle tactic was to form a shield wall, three or more ranks packed closely together, protected by shield, spear and sword.

This formation allows for a gap in the front rank caused by a fallen warrior to be quickly filled from the second rank - and so on. This is a nominally a defensive formation, but when one shield wall is set in opposition to a second shield wall there are two potentially immovable objects and somethings gotta give!

Much, if not all, depends on holding the line of the shield wall, so initially neither side would want to make the first move.

Battle would likely have started with the hurling of javelins and exchange of arrow storms, and then the two shield walls would approach each other with the great noise of, banging of sword on shield, shouting and screaming of insults and each side looking for a weak point in the opposition wall which might be exploited.

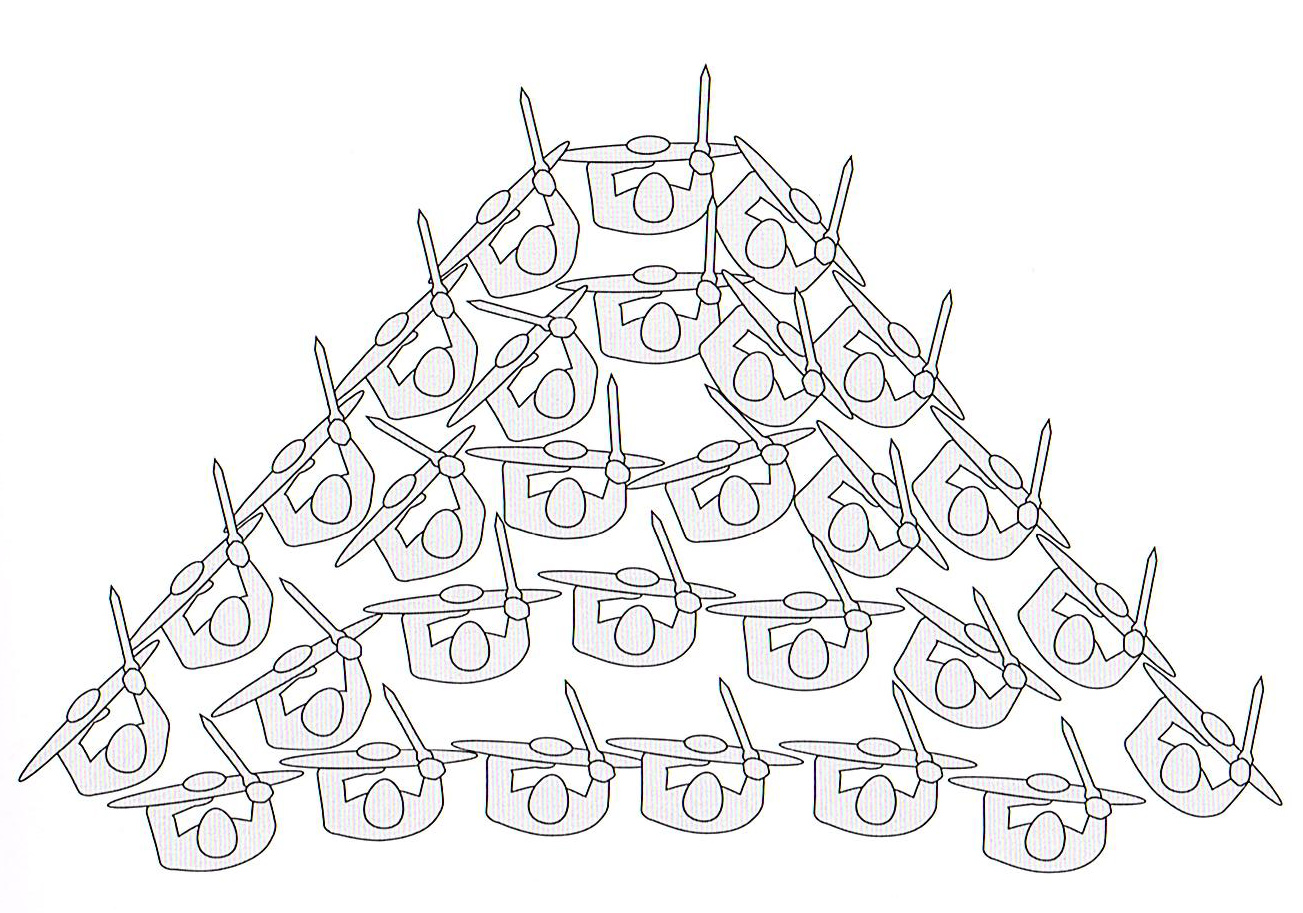

The larger force might of Malcolm and Owen, might have attempted to overcome the Northumbrians by sheer force of numbers and use their superiority to crush line or outflank the defenders and attack into their rear. Another tactic was to use the Boar’s Head formation to break through the Northumbrian defensive line by sheer force of numbers using the Boar's Head formation. This concentrates the attack at a point and drives a wedge through the defenders’ line which can then be exploited to great advantage.

The superior numbers of Owen and Malcolm made the outcome of this battle inevitable. The Northumbrians were defeated with heavy losses but Malcolm made no attempt to proceed further south to Durham to avenge his defeat of 1006.

This was the last mention in history of Owen of Strathclyde. He died in 1018 but we do not know whether he was killed in battle or died of wounds sustained there.

The Northumbrians suffered a sufficiently heavy defeat as to be unable to retaliate, but were the Northumbrian losses as excessive as Simeon of Durham claimed? Certainly the Northumbrians were in no position to retaliate and counter attack and Lothian, the land on the north side of the River Tweed was not regained.

Owen and Malcolm must also have suffered casualties, but were these sufficient to dissuade them from further advance? Surely Malcolm would have been eager to avenge his defeat of 1016 at Durham, but serious attempts at further southerly gains did not materialise until an attack on Alnwick in 1093.

A 30 minute documentery film, 'Carham 1018 - The Start of the Border Story' is now available to view on The Battlefields Trust YouTube channel.

A shorter 7 minute documentery film, focusing on archeology at Carham has been produced, and is now available to view on The Battlefields Trust YouTube channel.

Please consider making a donation to Battlefields Trust North East to allow us to continue our work on the Carham 1018 Project.